FACULTY: Dave Carlson’s “Long, Strange Trip” Comes to an End

By Tracy Wright, B.S. Public Relations 1999, M.A.MC. 2002

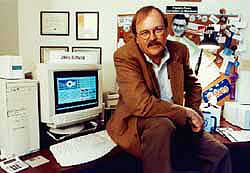

Dave Carlson’s office on the third floor of the UF College of Journalism and Communications perfectly reflects his professional career and personality. Every square foot of it is adorned with classic rock memorabilia and strewn with communication devices dating back to the 1970s. Those artifacts will be an enduring part of his legacy at the CJC, as Carlson retires after 25 years.

“I have the coolest job around, and some days I can’t believe I am walking away from it without a fight,” Carlson chuckles,”but it’s time. It’s time for a new stage of life.”

In the early part of his career, he held almost every journalism position in the industry as a reporter, editor and photographer on newspapers with circulations ranging from 7,200 to 430,000. As the Cox/Palm Beach Post Professor in New Media Journalism in the Department of Journalism, he taught undergraduate and graduate students about the electronic community, the future of mass media and, later, rock and roll history. But it’s his visionary work in online journalism that has set him apart as a pioneer and futurist.

It all started in 1981 in New Mexico, where Carlson was working as an energy and environmental writer traveling throughout the Southwest. One day his boss told him there was a package waiting for him at a bus station. When he picked it up, he found a Radio Shack Model 100 portable computer with a built-in modem that operated at 300 bits per second (the height of technology then). It included a pass to get 10 free hours on CompuServe, the first major consumer online service.

That night he labored for hours to log on (not an easy task in 1981) and, by 3 a.m., he managed to get in. He found the Associated Press Wire was available and jumped for joy in his living room.

“It was at that moment that I had my epiphany,” he said. “The wire in real time! Somehow, I just knew that this was the future of journalism. I drove my coworkers nuts with talk of my vision of the future and online media. They thought I was a kook.”

Fast forward to 1988 when Carlson was working at The Albuquerque Tribune and a different boss put up a flyer asking for a staffer to work 10 hours a week to develop an electronic version of the newspaper. It meant more work and no extra pay, but Carlson jumped at the chance.

Given a $5,000 budget, Carlson put together a rudimentary system on a rented computer, an IBM 286. When it launched in 1990, there were four incoming phone lines, meaning just four readers could be on the system at a time. His editor was hoping for at least 50 users that first day. They had more than 100 users in the first five hours.

The Electronic Trib grew quickly and generated a lot of interest in the industry. Carlson and his staff of one part-timer figured out ways to do things that hadn’t been done before. They were the first to put public records online where the public could see them without having to go to a government office. They also managed to come up with a way for users to order pizzas online, another first.

The Electronic Trib grew quickly and generated a lot of interest in the industry. Carlson and his staff of one part-timer figured out ways to do things that hadn’t been done before. They were the first to put public records online where the public could see them without having to go to a government office. They also managed to come up with a way for users to order pizzas online, another first.

In 1993, UF received a one-year grant from the Freedom Forum to hire a visiting professor to teach students about “the electronic newspaper.” The CJC and Dean Ralph Lowenstein recruited Carlson for the position, and the Interactive Media Lab was born.

“Typically, the people involved with experiments in this new medium were not editors, but techies,” Lowenstein said. “Dave stood above the relatively-few candidates at that time because he was a newspaper reporter-editor, with long experience at newspapers about the size of the Gainesville Sun. We were very lucky to find and attract someone like David Carlson.”

“In the fall of 1993, I remember two master’s students running into my office excited to show me Mosaic, the original graphical interface for the World Wide Web. It was the first browser,” Carlson said.

“Within a week, we downloaded some free software and built one of the first journalism servers in the world. That same night, we surfed every website we could find. There were only about 50 – in the entire world – and none of them we could find were journalism related.”

That spring of 1994, the College asked Carlson to join the faculty on a more permanent basis. He then led a team of students on Sun.One, a collaborative effort with the Gainesville Sun to develop an online newspaper template as part of a three-year, sponsored research agreement with the New York Times Regional Newspaper Group.

In 2000, he was instrumental in developing the Newswall, a bank of monitors in the Weimer Hall atrium that showed websites, television stations and an Associated Press newswire “ticker” featuring the latest local, state and national news. It was a full 20 feet wide, featuring 10 monitors, and it was dedicated on Sept. 10, 2001, the day before the Twin Towers fell in New York City. The Newswall instantly became a favorite spot for anyone passing through the College’s breezeway.

In 2006, under Dean John Wright, Carlson was appointed executive director of the Center for Media Innovation & Research, which was focused on creating new ways of telling stories, developing new means of disseminating strategic communications and researching the effectiveness of both. He oversaw creation and construction of the 21st Century News Lab and the Aha! CoLab.

While hesitant to call himself a pioneer, there is no doubt that the term futurist cannot be overstated when it comes to Carlson. He has consulted with America Online, Prodigy, eBay, Apple and Microsoft. He is the author of “The Online Timeline,” an authoritative history of online journalism.

Carlson has also been working since the 1990s to preserve the history of online media and journalism.

“There are no hard copies of digital media,” he says. “This is the first thing created by humans that has no permanent record. There aren’t printouts, drawings, or paintings. There is no papyrus. No scrolls, no nothing.

“Unlike many other types of history, this has not been documented and has no permanent record,” Carlson said. “We all worked as fast as we could to create the next thing, to advance, to incorporate whatever new thing came along, and nobody saved what came before. When I realized that, I started making and collecting screenshots of online media and videotaping sessions online.”

Carlson, needless to say, was highly respected by the news industry. He was new media columnist for American Journalism Review and he traveled widely, giving more than 100 presentations on five continents. In 2005, he was elected national president of the Society of Professional Journalists, the first educator ever to hold that post. In 2013, he was awarded the Wells Memorial Key, the highest honor for a Society of Professional Journalists member.

Another of his passions is evident the moment you walk into his office. Studying the history of music – and of course listening to the classics every moment he can – has been a major influence in his life. After the professor who developed the College’s rock and roll history course left, Carlson was tapped to teach it. The course covers the history of rock and roll and its effects on American culture. It ends with the breakup of the Beatles in 1970.

It was chosen to become one of UF’s first Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and has attracted tens of thousands of students from more than 70 countries. It still is available free of cost at https://coursera.org/course/musicsbigbang. The MOOC experience caused him to become deeply involved in online education, and he has headed up the CJC’s undergraduate online degree programs since 2014.

It was chosen to become one of UF’s first Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and has attracted tens of thousands of students from more than 70 countries. It still is available free of cost at https://coursera.org/course/musicsbigbang. The MOOC experience caused him to become deeply involved in online education, and he has headed up the CJC’s undergraduate online degree programs since 2014.

Now that he is hanging up his teaching hat, Carlson and his wife of 34 years plan to do a lot of traveling. First, they will tour the United States in a camper, and then they will spend some extended time in Europe. Longer term, they plan to spend a month each year in a different one of the world’s great cities, beginning with Paris.

When asked what he believes his legacy may be, Carlson reflected for a moment.

“I wanted to be a journalist from the time I received a toy printing press as a childhood birthday gift. I knew I wanted to make a living doing something that helped other people,” Carlson says, choking back emotion. “I hope I have done that. I hope I have made a difference in the life of this College and in the lives of the thousands of students I have had the pleasure to know.”

Posted: June 11, 2018

Category: Profiles

Tagged as: Dave Carlson